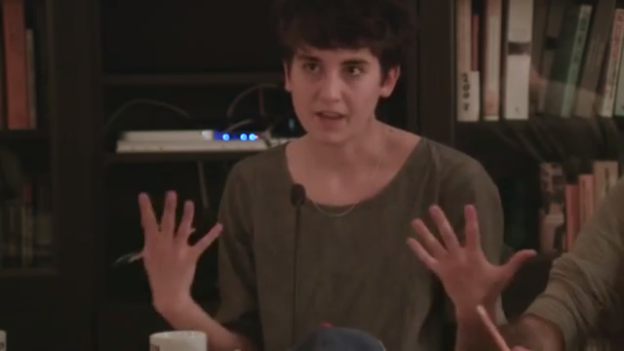

Basic income and jobs guarantee are often juxtaposed as two policies that are mutually exclusive, politically or policy-wise. Alyssa Battistoni, writing for In These Times, suggests that both are worth fighting for, and that the two policies could work in concert. Battistoni, a PhD student at Yale in Political Theory and editorial board member of Jacobin, spoke with Jim on how these two policies might work together.

——

Episode Transcript

Owen: Hello, and welcome to the Basic Income podcast. I’m Owen Poindexter.

Jim: And I’m Jim Pugh. Many of you have probably heard a lot recently about the idea of a job guarantee: a proposal where, rather than just giving people cash, the government would actually provide them with some sort of decent job that gives them a good wage and good benefits. There’s been more discussion about that from some Democratic candidates running for office, and the idea does seem to be picking up some steam.

Owen: Jim had a conversation with Alyssa Battistoni, a PhD student at Yale and contributor to Dissent, n+1, and Jacobin, on the idea that a jobs guarantee and a basic income are not necessarily mutually oppositional. Here’s Jim’s conversation with Alyssa Battistoni.

Jim: Alyssa, thanks for joining us on the podcast.

Alyssa: Thanks for having me.

Jim: There’s been an increasingly heated debate over the last few years between the ideas of universal basic income — providing everyone with unconditional cash at a level sufficient to bring them above the poverty line — and the idea of a job guarantee program, which would aim to provide a job with a living wage and decent benefits to any person in the country who wanted one. People generally seem to view these as two competing proposals for how to guarantee economic security to everyone.

You recently wrote a piece for In These Times that propose a combination of the two might actually be the best of both worlds. Can you walk us through your thinking there around the hybrid proposal?

Alyssa: Sure. As you say, the job guarantee/basic income debate has become a very contentious debate on the left, and these are rival ideas of how to solve the problem of unemployment, particularly after 2008 and the rise in unemployment that resulted. There are sometimes phrases: “full employment” as the job guarantee proposal or “full unemployment” being the UBI where people say, “There’s not work to do, we would we just make jobs?”

It’s always seemed to me that these are proposals that are trying to address the same problem essentially and that there are a lot of things that could be more complimentary, it doesn’t have to be completely opposed. I think there are a few ways to think about that. In the In These Times debate, there was one proposal for, one set of authors making a case for the job guarantee then another author making a case for basic income.

The case for basic income in that instance, this is Matt Bruenig arguing that UBI is a good thing. His version of the UBI is not intended as an income replacement or to be at the level of a full– to basically provide a full income to everybody. That’s premised on a more claim– the UBI is like a claim to public resources.

Obviously, the most famous example of this is the Alaska Permanent Fund, which always comes up in UBI debates. Matt Bruenig says everyone should have a claim to national resources of whatever kind. The most prominent examples are typically oil, gas, and mineral resources.

That’s actually something that I have a complaint with because I come to this from the prospect of thinking about environmental issues, climate change and wanting to use political economy and economic programs to address climate change. Thinking, I don’t want us to build a new set of universal social benefits on the back of fossil fuel. That seems like a bad idea to me.

But you could certainly imagine a version that was almost going the other direction, that I was trying to tax resource depletion or make other kinds of claims to public resources that aren’t necessarily extractive industries, up to and including things like– there’s been some proposals to do a version of that for the rents coming out of patents and things like government subsidies and so on. That would just be a more of everyone gets the money as a claim to public resources and you could pair that with some jobs program.

I also frankly think that you could just have a much more robust UBI that is actually an income replacement. If people really also wanted to work– job guarantee people say, “Well, people want to work, and we need to create jobs because everyone wants a job, and it’s good for people’s well-being.” I’m like, “Okay, if people want to work they can go get a job on top of their basic income.” That seems technically complementary possible.

The obvious problem is money: where these come from, how you do both. That is really the problem with certainly doing both UBI and job guarantee or with doing either comes in is the problem of politics and power and where we’re actually going to get those things for these both potentially quite radical transformative programs, how we can actually realize is a big question.

Jim: Yes. Definitely. I’m curious, what reactions have you gotten to your piece and to your proposal? Have you heard from both basic income and job guarantee proponents on how they feel about it?

Alyssa: On my argument that these can be complementary, I was pleasantly surprised, honestly, to mostly have people say they appreciated a perspective that was not as firmly in one camp or the other, that you can have some version that recognizes some of the complementarity. Part of that is also that neither is going to solve all the problems. For a while, there’s been UBI as the utopia that will fix all these problems, like Rutger Bregman’s book last year, Utopia For Realists, has this account of how a UBI will fix tons of problems from depression to climate change and so on. You see the same thing from the job guarantee folks a lot. It’s going to solve income inequality and racial disparity and all these things.

Both of them have the potential to make inroads and certainly policies matter, but frankly, I don’t think either of them is likely to just wipe away all the problems of contemporary American life and so we should take that into account. Certainly, the job guarantee idea is in ascendance on the policy left right now, and there’s been some proposals put out recently.

People have been amenable to particularly the environmental and climate critique of potentially– you have to be very careful what kinds of jobs you are creating and not just do a job creation and “any job is a good job” sense, which job guarantee is not necessarily saying, but the kind of language around just “jobs are good” can be the message. That, I think, is not a good message to be putting out. People recognize that they’re important points on both sides if you really make that case. I hope that we can do that.

Jim: Yes. I can certainly understand the appeal. If there are a lot of people out there who feel strongly that, “I don’t just want financial support. I need, I want to have a job. I want to have meaning, and I don’t have a path the one right now.” Then that certainly seems attractive from the perspective of a job guarantee because you are then guaranteeing it.

One concern I have—this actually is something that’s been raised by Matt Bruenig, and I’m curious if you have thoughts here. I do get the sense that there often are a conflation of two different programs in job guarantee discussions, at least, if not proposals: one being setting up the federal government as the Employer of Last Resort for anyone who can’t find a job, at least a job they like, in the private sector could always look to the government for work. Effectively a public option for jobs, and that’s where guarantee aspect of the program comes from.

The second being a large public works program, which if we’re talking about repairing crumbling infrastructure, tackling big projects that move us towards a green economy, generally important work that isn’t actually being handled through the private market today. So a new WPA, effectively. I think those both seem like really interesting proposals, but they also seem different because the Employer of Last Resort—inherently, if you have a guarantee, you can’t have a litmus test on experience or skills. Whereas if you want to take on big infrastructure, you probably do want people who have a lot of experience and skills if we’re actually going to do that right. I don’t know, is that something you’ve thought about? Do you have thoughts on that distinction?

Alyssa: Totally agree that that is an important distinction to make, and I also agree that that sometimes it’s conflated in discussions around job guarantee where it’s jobs programs that– it seems often there is an idea of a major jobs program that would also function as a job guarantee but also going above and beyond a job guarantee in many ways. Frankly, I have this feeling that there is a lot of work that doesn’t need to be done. We should figure out ways to move out of that and diminish work overall and let people have time for other things.

I also recognize that there’s a lot of work that we should be doing. I think actually quite a lot of that is, there’s both short-term jobs program, like short- to medium- term, like you said, infrastructural projects and things like that where you would want people who were committed to a project for the duration of the project. I also think there’s some very long-term jobs we might want to secure or work we want to make sure was done that the government was creating basically permanent jobs in or permanent work in, like a lot of the care proposals.

There’s been more recent job guarantee proposals: [the proposal] from Stephanie Kelton and Paulina Tcherneva has been very emphatic on care for people, planet, and communities, which I am totally on board with as modes of work. I think it’s very important to be supporting that work and giving decent jobs with decent wages and all that in that work.

I also think that that should be very long-term, not a tailored to cycles of the business cycle or job creation and unemployment or whatever. I want to just be like, “Okay, we’re just making a bunch of jobs, and they’re just going to be that and actually jobs that are good enough to crowd out a lot of private employment.”

I imagine there’s ways to design a job guarantee that has some overlap with a broader jobs program that could function together, but I do think sometimes the job guarantee has become the New Deal / WPA type thing, and I agree they seem like distinctive things, and I also would like to make sure that we– I think sometimes the job guarantee, in the less transformative versions of it, functions as a backstop to private sector job creation, and it’s one that does give people and workers more security certainly, more ability to demand higher wages and better jobs and so on. This doesn’t really control what kinds of jobs or seem to care what jobs are being created in the private sector.

If you think, as I do, that a lot of private sector jobs we don’t want to encourage, or we would like to replace private sector work with things that we think need doing like care for people and planet like that. It would be good to crowd out private sector employment in some respects. I think sometimes the job guarantee proposals I’ve seen or just like different ones have more or less of “This will stimulate private sector growth and employment and just be a place for people to hide out for a while while the private sector creates more jobs, and then they can get whatever job the private sector has created” versus “We have an economic and social agenda that we’ll try to– we’ll try to merge an economic and social agenda through the job guarantee.” I’m more favorable to that, but it’s certainly a more demanding proposal and one that I think goes beyond that base level.

Jim: Right, it does seem as though– while all of us are clearly thinking far beyond what is politically possible today, we do have our own internal thresholds, or it’s like, “Whoa, okay, no, that’s too big of an idea. Can’t have that combination or can’t have that particular approach.” I feel like there’s some interesting arguments that arise as a result of those different perspectives.

That was certainly also something that came up when I had my conversation with Jared Bernstein last year about his thinking on job guarantee is that he at times– and he recognized this during the conversation, but said, “We’re suspending political disbelief, but only to a point.” Where that leaves us is always interesting to see.

Alyssa: Yes, and it’s hard, because I think it’s important to have distant horizon utopian type ideas that are what we’re working towards and also some more pragmatic short-term view of how to get there. It’s one of the things that has been tricky in getting UBI off the ground, it seems to me, it feels like the left version of it feels so utopian, people can’t imagine how you would make it happen in the short term. it’s rethinking so much about work and production and how we expect that to function that it’s an easier sell politically in many ways to be like “Well, you get a job, and you contribute to society, and you get your good wage” and stuff like that.

I think there are ways to do that that are not totally just reinvesting in the dignity of work and work as the means to all social welfare that I think would be important to try to integrate into the job guarantee rhetoric. I also took the point that it’s hard to totally transform where people think about work and income very fast. That’s fair.

Jim: Right. With basic income, you’re not just talking policy change, you’re talking culture change.

Alyssa: Yes. Which I think needs to happen, but I also get that it will take a while and so figuring out ways to continue to not cede the ground of social rights and universal benefits and so on, while also recognizing that there is a long way to go to get– if anything, it sometimes seems like things that we’re retrenched since things like welfare reform and so on have demonized recipients of benefits as undeserving and so on.

Jim: On that note, you wrote explicitly in your article about the hybrid proposal that one of the main thing was that attracted you to basic income was that idea of separating livelihood from jobs. When I’ve talked to other basic income advocates, my strong sense is that is a powerful underlying driver for much of the support of the policy.

I think that maybe why there’s been such a strong negative response from many in the basic income space to the idea of the job guarantee program, because they do see that going in the opposite direction, and if folks — and I include myself in this as well — would like to see that conception of deservedness be decoupled from having paid jobs and that job guarantee is moving away from that, then that’s obviously a reason to not be supportive of the policy.

Then my question is, for the hybrid policy, let’s say that we could make this happen. I’m curious to get your thoughts in that scenario, do you think there would be then a natural shift towards separating deservedness from work or from paid jobs if that was an option for people or might we end up just entrenching these two camps of thought and we’d have the Sharks and Jets ongoing?

Alyssa: Yes. I definitely worry that the latter will happen, because it’s more politically palatable in the short term to do a kind of like “you get income if you do a job” thing, which people say everyone needs to do work, like it says in the piece. If the idea is everyone needs to contribute to society then that would be more like a mandatory work requirement program.

If you have a trust fund, you also have to get off your butt and go take care of the elderly or whatever, but it’s not that. It is explicitly to access livelihoods, you get a job and so that I do worry about. One of the things that I’ve been thinking is that there are certainly ways to structure for a job guarantee and basic income that oriented in different directions in terms of what vision of society it is holding up and aiming to achieve.

I do think that there are ways to try to use a job guarantee to put forth a different idea about what we think work is, how much work people should have to do, in a way that might be able to have a conception of work that’s more limited, that’s more widely distributed. I do think that that will be a political challenge.

Even if you have it like you have a reasonably, a lower reduced-hour work week or something and a high wage for reduced hours and increased leisure time and all of these things that have historically been part of Left approaches to work. You can have all of those things, but still, at the end of the day, to get access to these things and you have to have a job.

I still think that is a thing that we should try to– but that’s just going to be part of the job guarantee, so I do think that it’s very important to also be defending certainly what remains of welfare provision in the country, but I think also trying to advance that and to think about ways that we can increase access to unconditional benefits or even like semi-conditional benefits, like the child allowance is often discussed as a good kind of UBI adjacent policy. Obviously not everyone has a child and will unconditionally receive the child allowance, but just things that are increased social benefits.

One thing I mentioned in the piece that I also think is an interesting idea and have actually heard discussed very little in the US is the idea of universal basic services, which is people having access to public housing, free public transportation, and food stamps. A lot of the things that you actually need to live that you would have freely available.

I think it always can be helpful in solving some of the problems of the basic income, which are if you get X amount of money and then the private sector hikes up the cost of healthcare, housing so much that you can’t afford those things. This is one of the ongoing debates. If you just do in-kind service or good provision, people can still have the basics that they need to live whether or not it’s called income. Then that also seems compatible with a job guarantee. At the same time, it’s like– I still feel like at the end of the day, there are a lot of ways to try to make them more– to recognize that there are– to have a job guarantee that’s not just like “work is the greatest good of society.”

At the end of the day, I still think it’s crucial to insist that you shouldn’t have to have a job to be able to live and to have an income that you can live on, and all of that, and that your access to a livelihood. An economic mode that is premised on a lot of people not having access to a livelihood, that shouldn’t be at the basis of whether you’re able to live a decent life. I think it’s very important for the Left to insist on that, especially if we’re going for the job guarantee.

Jim: Your note on Universal Basic Services brings up an interesting point, which is beyond the question of deservedness, whether you have a job or not, one of the other, I would say, strong underlying drivers in the basic income space is the idea of choice. A lot of this, I think, has been certainly at least fueled by some of the research around unconditional cash that’s been done by GiveDirectly on others in developing nations.

Different people view it even more through a pragmatic lens or more through a moral lens, but it is often better to give people support in a way where they decide for themselves how they use that support. Hence the preference for cash over the services. Because with cash, yes, you are subscribing then to a capitalist market, but that provides a way for people then to choose for themselves, “Do I spend this on food? Do I spend this on rent? Do I spend this taking my kids to Disneyland?” That has a substantial value in itself. I’m curious what your thoughts are about that?

Alyssa: I’m sympathetic to that in some ways. I’m also suspicious of it in that I like both. I think a lot of the critique of certain aspects of the welfare state that come from the Left and from welfare recipients are around the paternalism of the welfare state and the 60’s and so on, where single mothers are being given a hard time by bureaucrats who are telling them how they should take care of their children and treating them like they don’t know what to do.

There certainly is a lot of that. I think actually, one of the reasons to make access to certain benefits more universal, coming with less terms attached is to minimize the degree to which you have people having to jump through hoops to get access to the things they need.

I guess my concern with the framework of choice is less that people shouldn’t be able to choose things. It’s more a couple of things. One is just the way that I think choice has become so– I think the framework of consumer choice comes very strongly out of a lot of neoliberal policy thinkers. This is the free-to-choose as Milton Friedman’s classic idea. It just frames the greatest decision-making power you have is as a consumer in the market and that is where your choice really lies.

I’m a little wary of just creating a program that’s like, “Okay. Well, that’s our paradigmatic value is.” Everyone has the freedom to choose in this sense that that means you get dollars to spend in the market. I do think that there are ways to be free to choose things about your life that if you have access to a set of things including housing, I don’t think that means that housing says you have to live in X place or Y place.

Hopefully, there’s ways to both choice into access to public goods and services, like free public transportation. You can choose where you go. There are many ways to think about choice that aren’t just like, “Here’s a dollar. Where are you going to spend it?” I do think the concern about what happens when people have a basic income and the price of goods is too high for you to choose those things.

Choice in the marketplace depends on how much money you have and how much money other people have to spend on things. I think that especially housing markets and healthcare seem like the most problematic for that. it can be so extreme if your choices are between two extremely expensive health care plans.

This is getting into the more like basic income as a replacement for all welfare state provision, but which is advanced under the banner of choice. It’s like, “Well, people can choose how they spend their money. If they don’t want to buy a health insurance, why should they have to?” Then you’re like, “What happens when people choose not to but they have cancer?” I think I would like to step back from that as the paradigmatic framework for how we think about how we choose things and what that means or what kinds of action that entails.

Jim: I do think your example with health care is a good point because most basic income advocates I know favor a single-payer solution on that. They don’t view healthcare as something that should fall under the auspices of what would be covered in the basic income, specifically because price is so variable that you’ve effectively eliminated choice on the supply side. From my perspective, a pure solution in either direction is very problematic. The question is, where do you draw the line as to what the market actually can handle versus what society should be providing directly.

I think this is a good segue into talking about– you mentioned in your recent piece that you’ve grown more wary of UBI, as you mentioned earlier in the conversation as well, as it’s gained prominence, in particular, due to who the visible champions are and some of the details of the policies being proposed. That touches back to your piece last year, The False Promise of Universal Basic Income, where you were cautioning those on the Left about supporting the policy. I thought you raised some really important points in that piece. Would you be able to just generally walk through your thinking around that?

Alyssa: Sure. Yes, this is a piece slightly misleadingly titled, because it’s more like “some warnings about potential basic income” rather than like “it’s a false promise totally.” However, I am more skeptical. I’d written a previous piece arguing for a UBI as a way to break the growth-job cycle and environmental climate proposal. I was like, “Okay, there’s been all this stuff coming out about basic income. I should see where the debate’s going” and so on.

As I was following the debate as it went on, I got more and more nervous that some of the rhetoric I was hearing, and particularly coming out of—not just rhetoric, but the policy ideas people are putting forward. I think particularly seeing how popular it was amongst Silicon Valley venture capitalist types, gave me real pause. One of the things that UBI people always bring up is that it has supporters on the left and right and there’s these different ideological trajectories. Maybe that makes it potential– you have this potential “big tent” of UBI supporters or something.

I don’t think the fact that there are people in the right who have supported a basic income idea disqualifies it at all. There are very distinctive versions. I was like, “What is going on here?” The more I came to think reading, for example, Andy Stern’s recent book, Raising The Floor on basic income, that it was being proposed basically as– for some people, it is a techno-futurist solution to automation, and there will only be a few gig economy jobs and then what are we going to do with all these masses of unemployed. There are these different competing anxieties about “Will the masses come for us wealthy venture capitalists? We should throw them some UBI to keep them calm.”

That is not I what I’m looking for in the UBI. There’s an idea of UBI as a way to basically have a baseline for the very low wages of the gig economy. You could be an Uber driver and make whatever crappy wages — they’re not even technically wages because they aren’t technically employees. You can make whatever you make on a ride, but the government will backstop that basically. It seemed like a public subsidy to shitty paying private sector jobs, which I think is also not whatever I want UBI to do.

Things that are along these lines, that are positing that basic income as a way to stave off a more egalitarian political economic framework and to deal with the problems of automation. That made me concerned and the thing that I came to think a bit about UBI is that the idea of it as you sometimes see in, for example, in Rutger Bregman’s book, that presents that was rational post-ideological idea that’s solution oriented or it just makes sense as a policy proposal and it doesn’t have an ideological valence, sometimes seems like the good thing about it, but I came to think it was not the good thing about it.

I think that there are a lot of ideological components built into different conceptions of the UBI, and it’s really important to articulate those. My version is actually very different from this other one, and it’s not just the same because we both think a basic income is good. Andy Stern has this imagined debate between Charles Murray and Martin Luther King, Jr., which I found baffling, kind of offensive, that they actually agreed on more than they disagreed on because they thought a basic income was good.

No, I just don’t think that’s true. I think people who are coming at this from the left. I really don’t want to say because there’s a few– because there are people want version of the basic income that I don’t like, this poisons the thing, in the same way that I don’t think that whatever Republicans trying to attach work requirements to food stamps should disqualify job guarantee proposals, which are not trying to do that, even though they both potentially have this work-oriented mode of accessing benefits.

But I think it’s important to be aware of that, to make clear distinctions. I wrote this piece saying, “Here are the things that concern me about the basic income.” I think in this more recent piece, I’m trying to remind the people who are firmly in the job guarantee camp to also be aware of those same things, because I don’t think that job guarantee proposals are workfare, but as people on the Right are calling for workfare, i.e. requiring work to access welfare and other kinds of benefits, that will be something that seeps into that debate whether people on the Left like it or not.

I think we just need to be aware of who are the people who will try to get in on the proposals we’re putting forth, how they will transform from the ideas we come up with and the ideal version – “this is all the good things about it, and this is how it could work.” Those things will change through the political process and particularly when…

Jim: The sausage gets made?

Alyssa: Yes, the sausage is not pretty as it gets made, but also we are not powerful enough like the people who have a Left UBI or Left jobs guarantee to just implement the one we want right now. Right-wing Republicans are very much in power right now, and it is going to be very hard to achieve the utopian vision of either of our policies. I think it’s important to remember how that might shift as things go through the political wringer.

Owen: That was Jim Pugh and Alyssa Battistoni on The Basic Income Podcast.

What I found interesting and insightful about that was that both basic income and jobs guarantee– they are aspirational proposals, and some of the detail can get left out sometimes. I think with both there is the small version and the big version, I’ll call them, where with jobs guarantee there’s, as you described it, there is the Job of Last Resort, where if you can’t find something else, you would still have this, and then there is the idea that you would be able to have a good, middle-class job through a jobs guarantee program.

Those are very different proposals. With basic income, you might see something with a few hundred dollars, maybe up to a thousand, or a true income replacement of $30,000, $50,000 a year or something like that. I think for jobs guarantees, those are very different proposals. For basic income, it is the same idea just more. Maybe people will disagree on that, but I found it instructive just to think through that.

Jim: Yes, I think that’s right. I think you see these different ideas out there, and depending the details you have it, it does make a really big difference. I think that– and this is certainly not true for every job guarantee advocate, you do hear people out there who are very specific in the version that they’re pushing. But there is sometimes this general conflation, and people wrap this up into some big general idea of a policy and then talk about what things that maybe some form of a job guarantee could potentially solve, but it all gets muddled into one.

I think that it does a disservice, I would say, to the idea of a job guarantee because it doesn’t allow you to really understand, “Alright, what are we talking about here? How does this connect to our core values?” It becomes hard to really have a good discussion on that in that case.

Owen: Yes, I think you can get away with it, when it’s a very far off thing, but now it’s being proposed by Democratic candidates for the House and State offices. Yes, I think it’s time to pick a path if you’re one of those people.

Jim: That’s not to say that we need every detail answered, because you can obviously make the same critique with basic income. There is a lot of specific questions that if someone were to say, “Ok, go. What is your national policy?” We wouldn’t have necessarily specific answers to. But I do think particularly the difference between Employer of Last Resort and just the general public works program, it’s not that those are details, those are really different policies. I really would like to see people make that distinction when they do talk about this.

Owen: One other question I would throw in there for a jobs guarantee people is, is this a program that works anywhere, where you live? Do the jobs come to you essentially? Or is there a difference between maybe a more robust public works thing that you might have to travel to and the guaranteed jobs is where you are? I think there are different ways to structure that and potentially some different good ideas in there, but that is a question that always comes to my mind.

Jim: Yes, I feel like most proposals I’ve seen have talked about local jobs, so that seems to be the thrust. But I think that’s also a good follow-up point, which is, if you are considering bigger infrastructure projects, that does likely require more people to move, so yet another reason why it doesn’t fit cleanly into an Employer of Last Resort model.

All that said, I think it’s important to say I personally agree with Alyssa. I don’t think that job guarantee and basic income have to be oppositional. I think that you could absolutely imagine a hybrid proposal where you provide a job to people who want them but then everyone is getting basic income, and there’s nothing wrong with that. If people actually like these jobs and want to take them, okay, they can do that. If not, they have basic income and can figure out their own path.

Owen: Yes, I feel like part of the opposition between these two ideas is the sense that we only have room for one big idea and that they address similar problems. But absolutely on a policy level, I’m just imagining how things would play out, there’s no reason these can’t fit together in the same world.

Jim: Just thinking politically, if you are a supporter of basic income, I think that there is very good reason not to come out hard against job guarantee or at least insist upon leaning into that in debates. because if we are talking about people who are in the general bucket of “thinking outside the box on how we actually guaranteed economic security for everyone,” there is going to be a good chunk of folks who maybe they were first introduced to the job guarantee, that’s what they are used to and so that’s what they advocate for. They could potentially be very open to basic income, but if it’s presented in a way that actually starts with their values, not as, “your idea is terrible, this is better” and so it becomes — it could really galvanize people into these two camps an unproductive way, I think.

Owen: Alright, that’ll do it for this episode of the Basic Income Podcast. Thank you to our producer, Erick Davidson. We are back, so we’ll have more episodes in your feed soon, and we’ll talk to you next week.